Nate handed me the keys to the 15-passenger van. “You’re comfortable with one these, right?” He asked. “This new one drives like a car, just give yourself some extra stopping and cornering room.”

I’d driven one of these vans in and around Minneapolis back in college, so I wasn’t worried about getting comfortable with it again, I just wasn’t expecting to be driving the van and trailer with a new student on my first day. Nothing like jumping in with both feet, eh?

A week before, I wasn’t even sure the job was still available. Rites of Passage Northwest (ROP) was experiencing a slower than usual summer season. Normally, they would be running three or four groups right now, but this year they had been bouncing between one and two. Less groups meant less guides, which was a problem for me since I was hoping for year round work and had turned down another opportunity in favor of ROP’s backpacking program.

Nate and his wife, Emma, started Rites of Passage Northwest about a decade ago, offering expedition style wilderness therapy treks to struggling youth and young adults in the Olympic National Park. Since then, they have grown to include an optional aftercare program at The Ranch, where students can live for up to a year while they work to put into practice the lessons they learned on the trail.

It was this dual approach of expedition style treks and available aftercare that drew me to ROP. I am eager to learn from their decade of experience in this field, to see how they have used journeying and wilderness to provide opportunities of growth and change to their clients.

More of which had signed up, thankfully, so hand me the keys and the maps, I’m just glad to be here!

“Here are directions to the trailhead where you’ll meet up with Group 2,” Nate continued. “Ariana and Lauren will walk you through resupply there. You’ll be swapping out with Lauren. Follow these directions to the next trailhead. It’s on the west side of the park, so it’ll be a bit of a drive.”

Taking the print outs from Nate, I settled into the driver’s seat while our new student bade farewell to her parents and loaded up in the van. After a quick check to make sure I had everything, I put the van in gear and headed up the driveway with a final wave to Nate and Emma.

I headed north on the 101 through little fishing villages to Hoodsport, where I turned left onto the 119 and drove out to the north end of Lake Cushman. Lauren and Ariana were waiting in a trailhead parking area with their students. As soon as I pulled in, we all got to work. We pulled out the resupply bins and started restocking bear cans, med kits, electronics, permits, maps, and more. One of the guides and a Family Phase student took our new student aside and outfitted her with her trail clothes and gear.

Our new student would start out in Individual Phase, which meant that she would spend most of her time alone watching the “nature channel” as they say. Most of ROP’s students don’t sign up for the program on their own. They are usually brought in by their parents, or sometimes by a transport group. So, the goal of Individual Phase is to protect the rest of the group from negative emotions often felt by these new students facing the challenges of wilderness therapy, as well as to give them a chance to understand why they are there and engage in the program.

Students meet with a therapist once a week who recommends when they are ready to move on to the next stage in their program. The field guides facilitate and monitor this progress, and have the authority to place students back into Individual Phase if they feel it necessary. Then the process starts over with the therapist.

There are three stages to the ROP program. Individual Phase, Group Phase, and Family Phase. The whole thing is meant to model the different levels of relationship that we find in family structures, and to practice participating in those stages in a controlled group. The wilderness setting helps shift paradigms, breaking students out of their comfort zones and challenging them with new obstacles that they have to work together to overcome. With a little bit of buy-in from the participant, it can be an extremely effective program.

Group Phase makes up the bulk of a student’s program. This is where they are doing the hard work of learning new skills, taking on camp chores, and digging deep into the issues and thought patterns that brought them to ROP. Each night, students and guides come together in a group council to discuss key topics or group related issues. It’s a dynamic way of sharing lessons learned and getting feedback on your progress and ideas. It’s really where the group work gets done.

At some point in their journey, guides will see students taking the initiative to serve the group without being asked. Natural leadership begins to arise as they become confident with their new found skills, and students will begin to find value in being helpful rather than confrontational or independent. That’s usually when they are ready to move up to Family Phase. They’ll take on new responsibilities and gain new privileges. For example, Family Phase students are allowed to know the time and see the map, and they may be called upon to motivate the team or pick a group council topic.

On my first shift, I had the privilege of watching a Family Phase student graduate the program, and I was able to move two Group members into Family Phase. I also participated in bringing a Family member back down to Individual Phase. All of it was done in council with my fellow guides and the therapist, and it was compelling to watch how it all worked. The students were genuinely excited to move up into Family Phase, and impacted when moved back down. And some of the connections that the students were able to make with their family life back home were truly insightful.

I understood that for this opportunity to work for me, I was going to have to give just as much as these students were. I was going to have to give my all and really show up for the next two weeks if I was going to come away from this shift knowing whether or not I was cut out for the work. Then I was going to have to go home and be fully present to my family, listening to them and observing how well this was working for them.

So I dove right in and fell in love with it all.

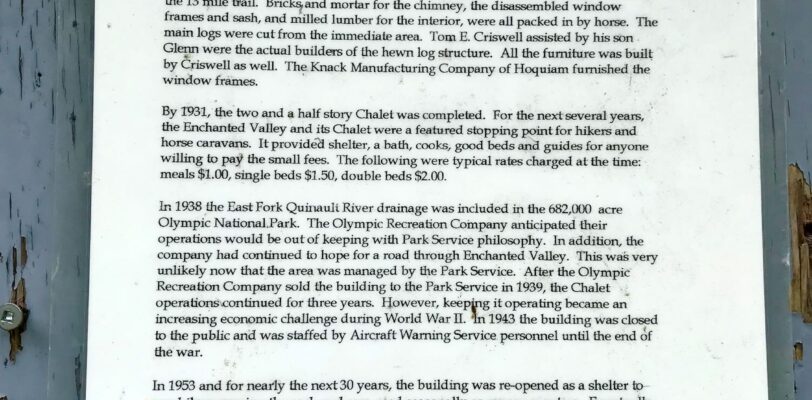

I spent my first week hiking through moss covered trees along the Quinalt River to the Enchanted Valley where waterfalls streamed down the 6,000 foot mountainsides and snow nestled on the peaks. The days were short on the trail and long on relaxing in the sun. I asked a 100 questions a day, taught object lessons, and drank coffee by the river in the morning. The kids were cooperative and engaged, and I was in no way properly prepared for my second week on the trail.

Erin brought a new student with her when she came out to relieve Ariana as trail guide. Things went well at first. Our new member was quiet and kept the pace, but she didn’t want to be there. The first campsite was only two miles in from the trailhead, so that was easy enough, but then a four mile hike to Elip Creek that would have taken us half a day last week took us all day this week. As new guides, Erin and I were not structuring a very strong Individual Phase for our newest student; consequently, we were about to see what happens when their unwillingness spreads throughout the group.

By day three trench foot and nausea were going viral. Our new arrival gave us a hike strike within the first hour of hitting the trail. That was closely followed by an all out panic attack from another student when she was faced with a large, fallen tree we had to crawl under. Our Family members were instrumental in both incidents, connecting with the students and encouraging them to press on. After all, there’s only one way to get to camp.

It was hard to tell how far we’d gone on the map which only made the day drag on more as the negativity and weariness settled in. Late in the day we had another hike strike, overcome largely with an appeal to cooking dinner as soon as we got to camp. Waning light, crumbling trails, and fallen trees only slowed us more, exhausting what reserves we had. We finally stopped to rest among the trees, and I ran ahead to scout the trail. We knew that we had to cross the river to get to camp, and I was hopeful because the trail was starting to go down towards the water we had been following for some time now.

It was sweet relief to see a campfire burning at the base of the hill. I went down and introduced myself to the lone hiker who was more than willing to help me out. He showed me where we were on his more detailed map, which happened to be a mile short of our destination, and told me about the trail ahead. It was more of the same fallen trees and another climb. Looks like we were staying here tonight.

I returned to the group and led them to camp. Before setting up, I called everyone to circle around.

“You guys have given far more than I could have asked for today,” I told them. “You’ve earned a rest day. I will not ask you to put your packs on tomorrow.”

The relief was palpable.

Erin and I needed the rest just as much as the kids did, and we were able to give it to them as a reward for those who had endured the hike with positivity and resilience rather than fight over it as a hike strike in the morning. That would have only fed the negativity.

We ended up staying at that campsite for two days to get back on track with our Park permit. That gave us time to bathe, wash clothes, and explore further up the trail to our original destination. We were able to work through the trench foot and illnesses, including a genuine fever, and everyone was in much better spirits when it came time to head back.

We shaved five hours off our hike time on the way back to our campsite at Elip Creek. The best part was watching the group decide together to press on just a little farther before lunch, and then encourage each other to hike strong all the way to camp.

The four mile hike that took all day on the way out was completed before lunch on our way back. That brought us to Wolf Bar and therapy day. And it brought me to the end of my first shift.

Nate surprised us by hiking out to meet us at Wolf Bar. The kids were excited to see him. I think they appreciated being a name and a face to the owner of this operation, not just another head count. We took a seat by the river and debriefed on how the last week went. I had kept Headquarters aware of everything going on via satellite, so nothing surprised Nate. Still, it was encouraging to hear him support our decisions on the trail.

“You are the boots on the ground,” Nate said. “You know what’s going on, and we trust you to make the right call. You’re the one who’s gonna know whether to push ‘em a little farther or to wait ‘em out.”

Then he told me about some crazy things that had happened to him on the trail. One kid could vomit on command, so he ate everyone’s food and threw it back up in their bear cans. Another kid defecated in Nate’s bear can. And once he sat in camp with a client for three days waiting out a fake injury.

“I said maybe four words to him that whole time and read like two books. He wouldn’t say a thing, but then after three days he cracked, and then I couldn’t get him to shut up! He just needed someone to talk to.”

Transport kids, run aways, hike strikes, vomit in bear cans…It’s not quite the soul centric work I see myself doing in the years to come. It’s more ground level than that.

With a chuckle, I told Nate, “Paul once wrote that some plant, some water, and some harvest, but here we plow!”

Nate laughed as we stood to rejoin the group.

Wilderness therapy as I have found it at Rites of Passage Northwest is not the second stage of life work I hope to do in the future; instead, it’s the ground breaking work of plowing the soil so new seeds can be planted. With that in mind, we have to be satisfied with scarred earth as the fruits of our labor. We cannot look for a full harvest where seeds have only just been planted, or where the ground has only just been broken open. Our reward is the heart broken open like the soil to the possibility of growth and change.

- For a quick read on what wilderness therapy is, how it got started, and the types of programs out there, check out this article on GoodTherapy.org.

- For a more in depth look at wilderness therapy, check out this article by Patrick M. Burns on Psychology Today titled, “Why Wilderness Therapy Works: The prescriptive use of adventure.” Burns goes into detail about his own experience with wilderness therapy, some stats on its effectiveness, and discusses some of its limitations.

- I spent my first shift with Rites of Passage Northwest. Here are some examples of what other organizations are doing in our corner of the world:

- And of course there’s Outward Bound, often recognized as the grandfather of wilderness work. With schools around the world, they seek to develop participants through skill building, experience, and education.

- Finally, if you have any questions for me about the soul centric work I mentioned in this post, or would like to discuss a Discovery Trek of your own, please do not hesitate to reach out through the contact from below.

Looking forward to new adventures! Buen Camino, my friends.

[…] lunch together on top of Coolwater Mountain in August. I learned how souls grow while serving as a wilderness therapy field guide. And finally, we brought the season to a close with an overnight trip to Stanley Hot […]

Your last paragraph is beautiful,…..”we have to be satisfied with scared earth…..” May your endeavors be fruitful no matter how small they may appear. A seed has been planted.

Thank you, Andre! Your words are encouraging.

This is awesome work! What a wonderful way to reach troubled kids. Beautiful country, but very taxing job. I know the rewards far outweigh that part. Keep on keeping on!

Thanks, Aunt Dee! I am getting ready to head out for my second shift, and I am looking forward to seeing how the kids have progressed since I’ve been away. There will be new faces, I will probably miss some who have gone home, but I look forward to journeying with those who are there and ready to explore the paths within. 🙂